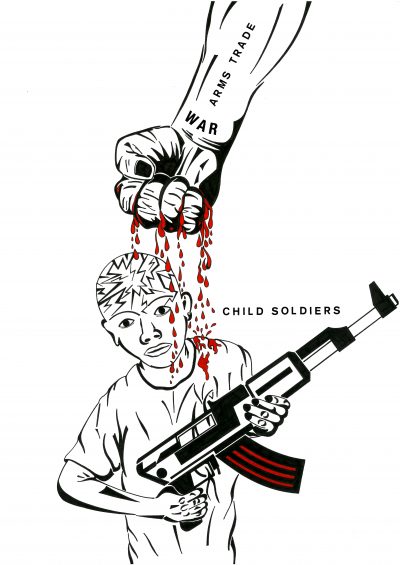

„We fought with your weapons!“ says a former child soldier in front of the UN Security Council, where the world’s biggest arms exporters sit. What is the connection between the suffering of child soldiers and the international arms trade? How do weapons get into conflict countries and into the hands of children, which countries and companies supply them? Which treaties and laws are violated even in many supposedly legal arms exports? And how can we take action to support child soldiers and stop arms exports?

GN Case 7 provides analyses, answers and demands, in-depth for two country examples: Colombia and Myanmar. Former child soldiers from these countries and from Uganda, Sierra Leone and Afghanistan have their say. The author Ralf Willinger from the child rights organisation terre des hommes Germany spoke to them and together they campaign for an end to the recruitment of child soldiers and arms exports. One of them, Innocent Opwonya, appeals: „Raise your voice for children’s rights, against violence and arms exports! Join the Red Hand campaign or become active in other ways!

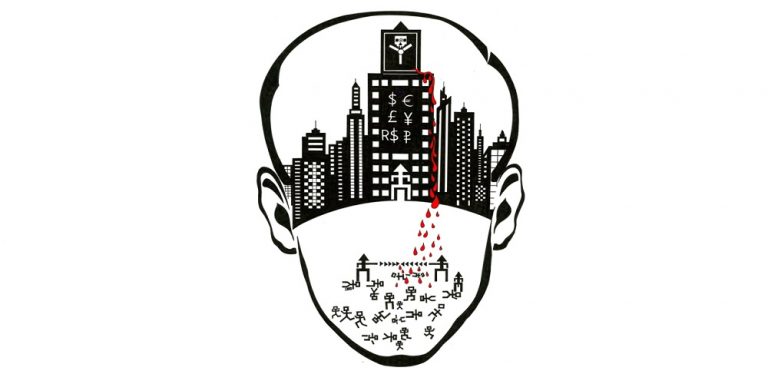

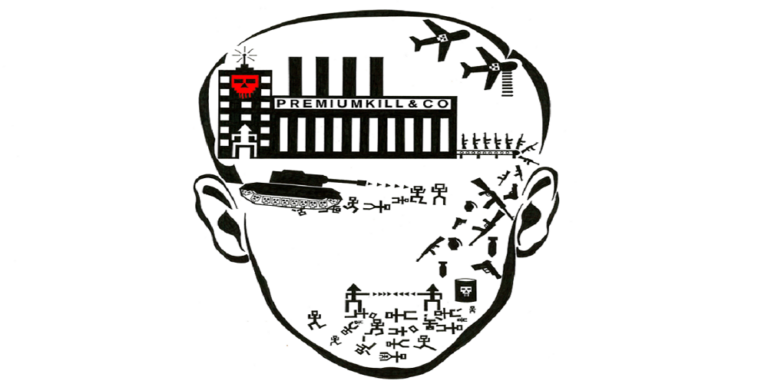

Image on the right: Haubi Haubner for the GLOBAL NET – STOP THE ARMS TRADE siehe „Artist Profile“

About this text:

Author: Ralf Willinger, terre des hommes Germany; Coordination: Helmut Lohrer, Jürgen Grässlin

Translation from German: Ruth Rohde

This text will be amended with further interviews and case studies.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

"I want you to get active!"

How child soldiers and arms trafficking are linked and how to get active on this

Innocent Opwonya is an impressive young man, tall, fine hands, alert, bright eyes. When he tells his story to the students, they listen spellbound, ask him questions, surround him after the lecture. The long scars on his legs are not visible. As a 10-year-old boy he was a child soldier, his rifle a German G3, he was desperate, wanted to escape at any cost. He made it, survived, one of a few, fought his way through, it was a long, hard road. Now, more than twenty years later, he hugs his newborn daughter and is overjoyed.

Every year, the „List of Shame“ appears in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on children and armed conflict[i]. The May 2021 report lists 61 armed groups and armies from 14[ii] countries that recruited, killed, maimeed, abducted or sexually abused children as soldiers or attacked schools and hospitals in 2020. In the body of the report, ten more country situations are reported where children have been abused in this way. [iii]

Map: Countries in which children are used as soldiers in armed conflicts

Graphic: terre des hommes; Source: UN Secretary-General’s annual report on children and armed conflict, May 2021

All of these countries are full of weapons, they have been supplied for years and decades, mostly directly by one or more of the six biggest arms exporters in the world[iv]: the USA, Russia, France, Germany, China and the UK – that’s the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany.

„We fought with your weapons“.

This is how the former child soldier Junior Nzita from the DR Congo put it in a nutshell in his speech to the UN Security Council in March 2015. Where the weapons in conflict countries come from and how they end up in the hands of child soldiers is presented in this case study for the two country examples Colombia and Myanmar – the two countries with the longest-running armed conflicts in the world, in which tens of thousands of children were and are exploited as soldiers.

Germany played a major role in building up the national small arms and ammunition industry in both countries in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as in many other countries in war zones – including Sudan, the country to which Innocent Opwonya was abducted by rebels[v]. There they trained him and gave him the Heckler & Koch rifle.

While I was fighting on the front line, I saw many different weapons. None of these weapons were produced locally, they all came from outside. The German G3 was the second most powerful rifle, you can kill someone at 500 metres with it. For children it was often sawn off so it wasn’t too long.“ Michael Davies, former child soldier from Sierra Leone[vi]

In the last decade (2011-2020), Colombia’s three largest arms suppliers were the US, Germany and South Korea; for Myanmar, it was China, Russia and India[vii] – and arms supplies continue, despite proven and ongoing serious human rights abuses by the state army and police and armed non-state groups in both countries.

Small arms are weapons of mass destruction

Small arms such as pistols, rifles and machine guns are used to kill and injure most people in wars and armed conflicts today[viii], and children are forced to fight with them. They are becoming lighter, are easy to use and cheaply available in conflict regions. They reach Colombia mainly via the USA, including many European makes[ix], and Myanmar often via neighbouring China and India.

„I want to see the recruitment of child soldiers outlawed worldwide. This includes stopping the manufacture and illegal trade of small arms, without which the use of child soldiers would not even be possible.“ Junior Nzita, former child soldier from the Democratic Republic of Congo

Is it permissible to supply weapons to countries where bloody armed conflicts have been raging for decades? Most people answer this question with a resounding „no“, as do former child soldiers like Michael Davies, Ismael Beah or Innocent Opwonya.

Treaties and laws are not being followed

Similarly, international treaties and laws such as the Arms Trade Treaty[x], the EU Common Position on Arms Exports or national export regulations of many countries[xi] prohibit this – they exclude arms exports to countries with armed conflicts as well as to countrieswith grave human rights violations . However, many exporting countries do not comply with these regulations because sanctions are lacking or not applied.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which regularly monitors compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, has also repeatedly called on arms exporting countries such as Germany to prevent arms from being supplied to countries where there are child soldiers.[xii]

The European Parliament, in its resolution of 11 February 2021 on the humanitarian and political situation in Yemen, stressed that “EU-based arms exporters that fuel the conflict in Yemen are non-compliant with several criteria of the legally binding Council Common Position 2008/944/CFSP on arms exports” and called for an “EU-wide ban on the export, sale, update and maintenance of any form of security equipment to members of the military coalition, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates”.[xiii]

In September 2021, the United Nations Group of Experts on Yemen (GEE Yemen) accused all warring parties of blatant violations of international humanitarian and human rights law and called on all countries to stop supplying arms and military support to the parties to the conflict. The expert group also calls on the UN Security Council to refer the situation in Yemen to the International Criminal Court. [xiv]

„If shipping documents are made public and people know which transport companies are shipping weapons to countries where wars are being fought and children are being killed, then it would be bad for business and the companies would have to stop shipping weapons. Because they ship many other goods and they need customers.“ Ishmael Beah, former child soldier from Sierra Leone and activist against arms trade[xv]

Unfortunately, however, the governments and companies of many countries continue to say yes to arms exports, including to crisis and conflict regions, thereby promoting war, violence, repression and the suppression of civilian protests. They thus bear part of the responsibility for grave human rights violations and war crimes such as the recruitment of children as soldiers. These connections have been known and obvious for a long time[xvi], but are not named enough and have hardly been prosecuted so far.

- In 2015, the Rwandan rebel leader Ignace Murwanashyaka, who had coordinated arms and ammunition transfers to the Hutu militia FDLR, was sentenced to many years in prison by a German court for aiding and abetting war crimes, among other reasons.

- A current case: Human rights organisations[xvii] have filed a criminal complaint with the International Criminal Court in The Hague in 2019. In it, they accuse European arms companies such as Airbus, Rheinmetall, Leonardo and BAE Systems [xviii] and state actors from Germany, France, the UK, Italy and Spain of aiding and abetting war crimes committed by the military coalition around Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Egypt in Yemen. Thousands of attacks on civilian homes, markets, hospitals and schools have been carried out, killing and injuring many people, including children. [xix] The members of this military coalition receive most of their arms from the USA and Great Britain, but also from France, Spain, Germany, Italy and other countries

Child Soldiers in Armed Criminal Groups

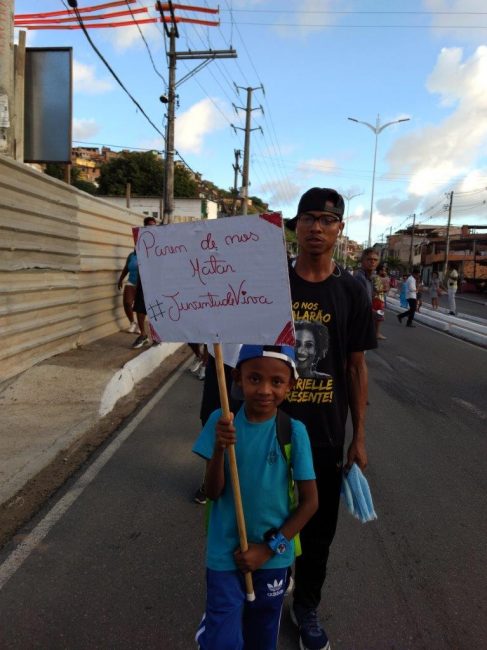

The UN Secretary-General’s annual report with the List of Shame mentioned at the beginning is an important instrument for exposing grave violations of children’s rights and naming perpetrators, but it also has shortcomings and large gaps[xx]: countries such as Mozambique, Ukraine, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, Nicaragua, El Salvador or Guatemala are missing from the report, although grave violations of children’s rights are also committed there in armed conflicts – by criminal gangs and armed non-state groups, but also by state actors such as the police and military.

For example, according to official statistics, police in Brazil were responsible for the killing of almost 6400 people in 2019, including over 1500 children and adolescents under the age of 19[xxi]. By comparison, in the same year, the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on children and armed conflict recorded the highest number of killings of children in armed conflict in Afghanistan, 874 cases.

When boys and girls are recruited by armed criminal gangs, they must be considered and supported as child soldiers just as when armed groups do so in warlike conflicts. [xxii] They clearly fall under the international definition of child soldiers or „children associated with armed groups“ in the Paris Principles for the protection of such children[xxiii]. According to these principles, a “child associated with an armed force or armed group” refers to any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities.”

Image: Stop killing us! Demonstration against police violance in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil. Photo: CIPO

This clearly also applies to girls and boys who are members of armed criminal gangs. The recruitment mechanisms and reasons why they are recruited are largely the same as for armed groups and armies in warlike conflicts: Children are cheap, easy to manipulate and available in large quantities; the recruiters simply take them or try to get hold of them with threats and false promises. Many children are also driven into the clutches of the recruiters by great need and fear of survival. There is no turning back; those who try to escape or leave are usually severely mistreated or killed.

Consequently, this means that weapons must not be supplied to countries such as Brazil, Mexico or Indonesia, where grave human rights violations take place and children are recruited into criminal gangs, just as they must not be exported to the 24 countries in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report (see world map) or to countries involved in wars in these countries (such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Egypt and other countries in Yemen).

Countries with child soldiers are among the biggest arms importers

But instead, such countries were among the world’s largest arms importers between 2016-2020: Saudi Arabia (largest arms importer), India (2nd), Egypt (3rd), United Arab Emirates (9th), Pakistan (10th), Iraq (11th), Indonesia (18th), Afghanistan (25th), Philippines (31st), Myanmar (33rd), Mexico (35th), Brazil (37th). [xxiv] Not only war crimes, but also political murders and massacres are often committed with foreign weapons in these countries, such as the killing of the Afro-Brazilian city councillor Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro in 2018 (murder weapon: MP5 machine gun from Heckler & Koch) or the massacre in Ayotzinapa in Mexico in 2014, in which 43 students were murdered, among others with German G36 rifles from Heckler & Koch.

List of shame for arms dealers

Conclusion: Arms exports to countries with armed conflicts and grave human rights violations must be outlawed and prohibited by law. As for the recruitment of children, there must also be regular monitoring reports by the United Nations and a list of shame that names and shames black sheep . In the case of arms deliveries to such countries, it must be investigated whether they are aiding and abetting war crimes and grave human rights violations, and those responsible must be prosecuted and brought to justice.

Demands for Red Hand Day

Civil society and human and child rights organisations have been calling for this for a long time. The three main demands for Red Hand Day the annual child soldiers‘ day of remembrance, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year, are:

- Stop the recruitment of young people under the age of 18 as soldiers.

- Stop arms exports (especially small arms and ammunition) to conflict regions and countries with grave human rights violations such as the recruitment of children as soldiers.

- Prosecution of those responsible

„Raise your voice against violence and arms exports!“

Innocent Opwonya has been campaigning for these demands for many years on Red Hand Day at public events, school visits and press conferences. „I don’t want pity. I want to get people to take action,“ says the former child soldier and activist. „In democracies, everyone has a voice, and that’s where it matters to raise it and use it, for children’s rights. And against violence and arms exports. Talk about it with your families, with your friends, with politicians, words can make a big difference. Join the Red Hand Campaign against the use of child soldiers and arms exports. Or get active in other ways!

Image: Red hands in front of the German parliament: Innocent Opwonya at an action against the use of child soldiers on Red Hand Day, Photo: terre des hommes

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Child Soldiers and the Arms Trade: Case Study Myanmar

„I was so sad that day. The officer was watching us and if we didn’t run, he beat us. My friend died because of the drill,“ says a former child soldier in the Myanmar army.

A coup against the democratic government in February 2021 and imprisonment of the head of government Aung San Suu Kyi, massacres of its own people, genocide against the Rohingya and brutal violence against other ethnic minorities – the list of offences committed by the Myanmar military is long. This also includes the systematic recruitment of child soldiers. Myanmar has long been considered the country with the most child soldiers worldwide. It is estimated that thousands to tens of thousands of children and young people under the age of 18 are fighting in the state army and armed opposition groups in the Southeast Asian country. Even ten-year-old boys and girls are recruited or exploited as forced labourers. After falling for a few years, recruitment numbers rose sharply again from 2019 – and after the military coup in early 2021 and the subsequent escalation of violence, this trend has probably continued.

Image: Child Soldiers in Myanmar: The army and non-state actors are exploiting children as soldiers and workers. Photo: Hans-Martin Große-Oetringhaus, terre des hommes

„I saw so many people die right in front of me and I was filled with fear. Those images are still a nightmare for me.“ [xxv]Child soldier from Myanmar who was recruited at the age of 12

The army recruits a record number of children

According to the so-called „List of Shame“ in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on children in armed conflict of May 2021, both the state army and at least seven armed opposition groups in Myanmar are using children under the age of 18 as soldiers. According to the report, the UN documented nearly 800 cases of children and adolescents being recruited as soldiers in 2020 (778 boys, 12 girls), the vast majority by the state army (726) – by far the highest number since the UN began documenting this in 2000. In addition, the report found that 64 children and adolescents were recruited by non-state armed groups in 2020 (Kachin Independence Army (62), Arakan Army (2)). The documentation of recruitment cases is very difficult, there is a high number of unreported cases. The figures for 2021 are not yet available – due to the numerous military actions and fighting after the military coup at the beginning of February, it is to be expected that they have increased further.

The same applies to other serious violations of children’s rights, such as the number of attacks on schools and hospitals (2020: 11) and their military use (2020: 31), as well as the number of children killed and maimed in the armed conflict (2020: 216). The state army was also predominantly responsible for these offences – through the use of landmines, bombardments, air strikes and crossfire.

Progress and regression

These are serious steps backwards after a temporary positive trend following the signing of a UN action plan in 2012, in which the Myanmar government committed to ending the use of child soldiers. In 2015, it also signed the Additional Protocol to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, and in 2017 the Paris Principles on the Protection of Children from Recruitment and on the Reintegration of Child Soldiers into Civilian Life.

Despite these positive signals, the efforts of the government and the military remained half-hearted during these years. For example, certain incentives for recruiters were not abolished. terre des hommes research on site revealed that military and civilian recruiters (so-called brokers) continued to receive rewards for new recruits and pressured minors into recruitment with threats and false promises. There were also many cases of passports and birth certificates being crudely forged so that minors were 18 years old on paper. Spontaneous UN inspections of barracks and military facilities to check whether child soldiers were present were not possible at any time after the signing of the UN action plan.

„We recruited children. We approached them in the harbour, at railway stations and bus stations. Our target groups were teenage street vendors, beggars and school-age children hanging around on the streets. We told them about the benefits of being a soldier, a good salary and other perks like rice and oil. We often went to the countryside to collect children, mainly orphans and street children,“ said a former recruiting officer. Many children also reported that they were threatened that they would go to prison if they did not come with them to the recruitment office.

Where do the weapons in Myanmar come from

Although the country, which was called Burma until 1989, has been marked by armed conflict and serious human rights violations since 1948, it was massively rearmed by Germany from the 1950s until the 1980s. Due to exports from the German arms companies Rheinmetall and Fritz Werner (a manufacturer of machines for the production of weapons, ammunition and tools), the Burmese military regime was able to reproduce the G3 in its own factory from 1964 onwards. [xxvi] From then until the end of the 1980s, the G3 assault rifle was the standard weapon of the Myanmar armed forces. [xxvii] With German help, production facilities for ammunition, rifles and machine guns were set up in Burma for decades. [xxviii] It was not until 1988 that German arms export licences were no longer granted due to „domestic political developments“. Subsequently, the Burmese military regime decided to cooperate with Israel in developing the successor model of the G3. [xxix] There has been an EU arms embargo on Myanmar since 1991. [xxx]

Today, China is Myanmar’s largest arms supplier, far ahead of Russia, India, Israel and Ukraine. [xxxi] According to Greenpeace research from February 2021, the Myanmar military uses Israeli patrol boats equipped with MG3 machine guns from the German manufacturer Rheinmetall, which were delivered from 2017. [xxxii] According to UN data, the Myanmar navy has also used boats in serious human rights violations and the genocide of the Rohingya. The human rights organisation Justice for Myanmar criticised ongoing arms deliveries to Myanmar by UN Security Council members in late 2021, citing a Eurocopter from the Franco-German Airbus Group, a Chinese Y-12 aircraft and Russian Yak-130 fighter jets as recent examples.

Due to the armed violence and serious human rights violations by the Myanmar army, in May 2021 more than 200 civil society organisations initially called for a halt to arms deliveries to Myanmar and a global arms embargo. [xxxiii] In June, the UN General Assembly joined this demand, and in December, the USA and the EU. However, Myanmar’s major arms suppliers, such as China, Russia and India, do not want to know anything about this and have continued deliveries even after the military coup. [xxxiv]

Release of child soldiers

According to the UN, 1015 child soldiers have been released from the state army by the end of 2020 since the signing of the action plan in June 2012[xxxv] – a ray of hope, but far from sufficient, especially in view of the recent sharp rise in recruitment figures. Underage deserters also continue to be detained by the army and in some cases mistreated.

The Kachin Independence Army, an armed opposition group, has also released underage fighters from its ranks in 2019 and 2020. And in November 2020, for the first time in Myanmar, an armed non-state group, the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army, signed a UN action plan pledging to end the recruitment of children under 18 as soldiers. This is an important step towards better protecting children, who are also heavily recruited by armed opposition groups in conflict areas such as Kachin State, Rakhine State, Kayin State and Shan State. Civilian organisations are also in contact with armed groups and educate them about human and children’s rights, partly with success: several groups have made a written commitment to no longer recruit children and young people.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Interview: "My G3 rifle was as big as me"

Innocent Opwonya, 31, was abducted at the age of 10 and forced to fight as a child soldier in the Ugandan civil war. Today he lives in Germany and has been campaigning against the use of child soldiers and arms exports for several years together with the children’s rights organisation terre des hommes.

I was born when the war in northern Uganda was already underway. If you were born during that time, war was a natural part of your life. Hearing gunshots every day was something normal, almost like breathing. Even though I knew nothing but war, it was a normal life. That changed when I turned ten. We walked from the countryside to the centre of Gulu every night, because we knew that the centre of the city is where the rich politicians live who can afford to pay for their security. We slept under their verandas so that we could use their protection for the night. But that was not the case when I turned ten, because that day it was raining very hard and my parents said we would sleep at home in our village. I thought to myself, it will be fine, but this was the day of misfortune.

Image on the left: Together against the recruitment of young people under 18 as soldiers. Innocent Opwonya and Ralf Willinger, terre des hommes. Photo: terre des hommes

The door was kicked in, a rifle pointed at my head

My sister and I slept in one hut and my parents in another. I heard a knock on the door. It was soldiers from the LRA (Lord`s Resistance Army). They ordered us to come out. But before we could open the door, it was kicked in and a gun was pointed at my head. I only saw the front part of the gun because the torch was pointed directly in my face. I came out and they tied my hands behind my back. Other children who were outside were tied with a rope around their waist, and with the same rope they tied the next child. We marched a long way that night because they were hiding in South Sudan near the Ugandan border.

The second night I was very tired and tried to call for help. They got very angry because this might attract the government soldiers. When my father tried to help me, they took him away. I heard a gunshot. At that time, I felt that I wanted to be a soldier now because they took my father away from me and I wanted to take revenge for that.

That changed during the military training. There they pointed guns at us, and we had to crawl into a trench as quickly as possible and escape. If you weren’t fast enough, you had to repeat the exercise all day. And if you didn’t pay enough attention and looked too far out of the trench, the shots hit you. In the trench I smelled the blood of children who had been injured. Out of about 60 children who were taken with me, 18 died in the first two weeks of training. We were also forced to take drugs to make us more obedient and determined for the many fights. I realised that maybe I didn’t want to be a soldier. Actually, I just wanted to go home. But that was not possible. So, I became a soldier.

They gave me a rifle, a G3, that was as big as me. That was the saddest day in my life. It destroys lives. I found out later that it is made by the German company Heckler & Koch from the Black Forest, which is terrifying. These arms exports must be stopped.

I thought I would never walk again

I desperately wanted to escape, but my first attempt failed, the boy on the watchtower had discovered me, and as punishment I was badly beaten, I was paralysed for a long time and thought I would never walk again. I still have big scars on both legs. Luckily, I had a good friend at the LRA, a boy from my village, he got me all kinds of medicine. That’s how I survived.

I was particularly saddened by the fact that there were many children of all ages living in the camps who had been born there and were brutally educated and manipulated. They knew nothing else and thought this was home. Sometimes we had to kidnap girls, they were also part of the children’s units. The commanders also picked some as women and took them to their camp. There was a lot of sexual violence. Some of the girls were only 10 years old.

Then during a battle with government soldiers, I made a second escape attempt, and this time I was lucky. It was an overwhelming feeling of happiness when I was safe. But that was quickly gone when the government soldiers asked me if I didn’t want to continue fighting with them. But they didn’t force me. I just wanted to go back home, to my mother. At first, I was sent to a camp for a few weeks, where I also got psychological help to deal with my bad experiences. We learned again what life is worth and that there are people in our communities who still care about us, who need us and love us – even when we thought it was over. That helped me a lot.

After my father died, the whole world seemed to end for me because he had been the sole breadwinner. My mother had to fight to survive every day with my sister and me. Many former child soldiers are suicidal for a long time. Not because they miss their weapons, but because they feel as if they have lost everything. On her own, my mother couldn’t make it, so my sister and I couldn’t go to school anymore and instead started working with her in fields and farms to earn our daily bread. I was very lucky to get a scholarship for secondary school and university. Unfortunately, my sister was not so lucky.

My scars remind me of my task

When I see my scars today, they remind me of who I once was and that this is a part of me. And that I was born for a task that is bigger than me: I stand up for children who have taken my place and are exploited as soldiers in wars. I wrote a book about my story together with a writer[xxxvi]. And I tell many people what I have experienced. Before that, I always talk to my mother on the phone, which gives me a lot of energy and self-confidence. And even though I have been living in Germany for a few years now, I still have a lot of contact with my family, including my sister and half-siblings. I did a master’s degree in economic policy in Germany, I’m married, and I recently had a little daughter, which makes me very happy. Only my nightmares in which I am being chased and have to run for my life, I would like to get rid of those. But I think they will be with me for the rest of my life.

Raise your voice for children’s rights! Get involved!

I don’t want pity. I want to get people to get involved. In democracies, everyone has a voice, and it is important to raise it and use it for the rights of children. And against violence and arms exports. Talk about it with your families, with your friends, with politicians, words can make a big difference. Join the Red Hand Campaign against the use of child soldiers and arms exports. Or get active in other ways!

You can find another interview with Innocent Opwonya here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFHG-DW_FDI (Accessed 24.01.2022)

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

"This must never happen again to a single child anywhere in the world. Never again!"

Yina was recruited as a soldier at the age of 11 by Colombia’s largest guerrilla organisation at the time, the FARC. Today she is an adult, works as a nurse in Colombia’s capital Bogotá and has a son.

Interview: Knut Henkel, Ralf Willinger

My family is from Tolima, I grew up there in a small village surrounded by mountains and the guerrillas have always been present in this region. It was not unusual for guerrillas to come to our farm. I grew up there with my siblings with my grandparents and with several aunts and uncles. Sometimes my mother was there too, but only rarely.

Our whole house was full of guerrillas.

We children had to work a lot, we were treated badly. One day, I was eleven years old, we came back from working in the fields at noon and the whole house was full of FARC guerrillas. They suggested to my aunt, who was a year older than me, and me to go with them and we agreed. We couldn’t stand it at home anymore because we always had to work and were beaten. The guerrillas assured us of good treatment and asked us to claim to the Comandante that we were at least 15 years old. We did so, and a little later we were accepted, after the Comandante had explained the most important rules to us. We were not the only children who joined this FARC unit that day.

I got along well with the rules in the FARC camp, adapted and had no difficulties. And my aunt Jazmin was there too. But then she was killed in a battle with the army. That hit me very hard. Our job as a mobile column was to support the various units, the frentes. We were the mobile reserve and there was always fighting in the region because the army and also the paramilitaries were present in the region, and they took action against us together.

Image: Hundreds of Thousands of red hands in New York: Yina, former child soldier, presents red handprints to former UN secretary general Ban Ki Moon, Photo: Ralf Willinger, terre des hommes

I was really scared at the beginning. I still remember my first battle in a small town, where we attacked the police post. My knees were shaking then, but later it subsided. After three years with the guerrillas, I was arrested by the police after a battle.

Many think we are a threat

Young people who leave armed groups cannot return to their families because they risk being killed by their former groups. Also, many in the communities think that we are a danger to them. They blame us no matter how old we were when we joined the armed group. After my capture, I was first placed in a state institution and then, like other former child soldiers, I joined a theatre group of the taller de vida project in Bogotá. Through theatre, I learned to reflect and express myself. For children and young people like me who were child soldiers, psychological help and support in building a perspective for the future is crucial.

I liked the theatre work so much that I continued and now work with children myself at taller de vida. It’s fun and we don’t just offer the theatre workshops, we also take care of the children, talk to them about the problems at home and at school and try to support them. Many children are alone after school because their parents work. We make sure that these children are not recruited by the guerrillas or the paramilitaries. Taller de vida cooperates with schools to offer something to the children and young people – not only theatre, but also dance and music, especially rap.

Today I am an example for others

Today I know that I was cheated out of my childhood by the guerrillas. But I only understood that over the years and art, theatre, helped me a lot. I discovered myself and only slowly understood what I was doing. I have learned a lot, have matured and today feel like an adult woman with responsibility. The work with taller de vida has helped me a lot. Today I am an example for others because I have made the leap, because I have built a new life for myself and because I can talk about my past. I have become more self-confident and enjoy my life. I lead a completely different life and determine it myself, and it is no longer determined for me. That makes me proud.

I live together with my child and my sister in a flat in a suburb of Bogotá. The child’s father is a former child soldier just like me, but we don’t live together. I take care of my child alone. That is not always easy, because there are also people who discriminate against us former child soldiers. But I don’t mind that anymore, because I have found my way and know today that I have rights. And I have also learned to make use of them. I brought my sister to Bogotá so that she wouldn’t have the same experience as me. Because in the rural area where I lived, the guerrillas are the state. People do what they say.

Red hands for the UN Secretary-General

For me, taller de vida is like a second family. A family that forgives, because I have made many mistakes and I have been given a second chance. A real chance. With the help of taller de vida and the child rights organisation terre des hommes Germany, I was in New York a few years ago to talk about my experiences and our work. And to present the UN Secretary General with red handprints collected in Colombia and over 50 other countries as a protest against the use of child soldiers. In our country, Red Hand Day is quite well known, but especially parents need to be further sensitised. It is important that people everywhere know that there is an armed conflict in Colombia and that children are being recruited as soldiers here and in other countries. This must stop! No child or young person should experience what I went through! Never again!

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

New Hope for Peace

Child Soldiers and the Arms Trade: Case Study Colombia

Image: Druming in the „children’s republic“ in Bogotá, Colombia: In the aid project Benposta, that is supported by terre des hommes, children from regions of conflict can find shelter, among them many child soldiers. Photo: Florian Kopp, terre des hommes

“The man shot, but the gun was not loaded.”

„Eventually an EPL commander came in who liked me a lot. He said if I want to learn something, I should do it. But I should not betray anyone. Loyalty is the most important thing, he said. If you are not loyal, they kill you. They test you. They disguise themselves as army soldiers. Once they sent me off on a moped with three kilos of „goods“ and 50 million pesos in a bag. Suddenly there is an army checkpoint. They arrested me and asked me what I had. They asked me to give names. They put a gun to my head. I remember very clearly how they said: Tell us who your clients are or we will kill you. I said: No. If you want, kill me. The man shot, but the gun was not loaded. So, I proved my loyalty, it was a test.“

Juan Andrés (name changed), 18, was born in the Norte de Santander department into a family of small farmers. He started working for the guerrilla organisation EPL (Ejército Popular de Liberación) when he was twelve. For three years he was a „miliciano“, passing on information and smuggling coca paste. For one year, he served in the fighting force. Then he managed to escape and has been living in the „children’s republic“ Benposta on the outskirts of Bogotá for two years. [xxxvii]

The Colombian government estimates that about 14,000 boys and girls have been used as child soldiers by armed groups in Colombia over the last 20 years[xxxviii]. The youngest child soldiers are less than ten years old; they are used for aid work, as scouts and messengers, and from the age of about 10 they are also used as fighters.

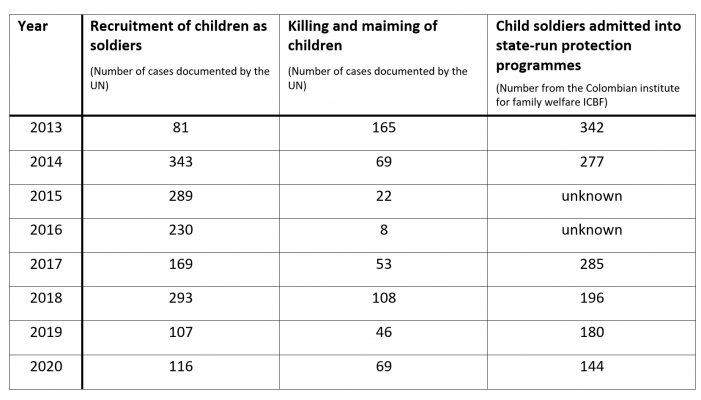

The peace agreement signed in 2016 between the state and the FARC guerrillas did not bring the peace that had been longed for, nor did it bring an end to the grave violations of children’s rights such as recruitment, killing and maiming – they decreased during the peace negotiations, but then increased again (see Table 1). This is because after the disarmament of a large part of the FARC guerrilla fighters in 2017, the state generally did not take control of their territories as promised, but paramilitaries, criminal gangs and guerrilla groups such as ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional) and EPL did, and there was increased regional fighting and recruitment.

Increase in serious child rights violations after peace agreement

The United Nations documented a peak of 343 cases of recruitment of children under 18 in 2013 for Colombia. After that, the number of cases dropped in subsequent years to 169 cases in 2017, the first year after the peace agreement. [xxxix] But the very next year, they rose sharply again to 293 cases – that year, the new government of President Ivan Duque of the right-wing conservative Centro Democrático came to power from August onwards, seeking to amend parts of the peace agreement and stepping up military offensives, including bombings.

As a result, in the same year, 2018, the number of children killed and maimed in the armed conflict also rose to 108, the highest figure since 2013, up from only 8 in the year of the peace agreement, 2016. In 2019, this number dropped to 46, rising again to 69 in 2020 (see Table 1).

Recruitment has increased since the start of the Corona pandemic. Colombian child rights organisations and the United Nations speak of a „recruitment offensive“[xl] – also encouraged by school closures, as a result of which protection by schools and teachers temporarily disappeared.

The number of girls and boys who were child soldiers of armed groups and were included in the state protection programme of the Colombian Institute for Family Welfare (ICBF) fell from 342 in 2013 to 144 in 2020.

Table: Ralf Willinger / terre des hommes, based on the UN Secretary-General’s Annual Reports on Children and Armed Conflict 2014-2021. For the quality of the data and unreported figures: see endnote [xli].

Great success: Children’s rights in the peace treaty

A great success of Colombian child rights organisations such as Coalico and Benposta was that they and affected children were able to participate directly in the peace negotiations in Havana, and thus aid and protection measures for child soldiers were anchored in the treaty and subsequently implemented.

However, many other agreements of the peace treaty were not respected, land distribution hardly took place, and the state did little for the security of the approximately 7,000 disarmed ex-guerrillas. Since the peace agreement came into force, 250 disarmed former FARC fighters have been killed by right-wing death squads. Disappointment with the peace process and the high risk of being murdered drove many ex-guerrillas back into the fight: according to estimates, around 3,000 of them have now re-armed and joined FARC dissident organisations or other guerrilla groups.

Police violence against protesters

According to the United Nations[xlii], over 400 human rights defenders, leaders of communities and social organisations, have been killed in Colombia since 2016, fuelled by poor state protection and underfunded prosecutions. In autumn 2020 and spring 2021, thousands of mostly peaceful, nationwide demonstrations for education and labour turned violent, with police and armed civilians brutally attacking the mostly young demonstrators. [xliii] According to the United Nations[xliv], which called the state’s use of force „unnecessary and disproportionate“, at least 52 people were killed, 1661 injured, 27 are still missing, and at least 60 women were victims of sexual violence by police. [xlv] President Duque rejected the accusations against the police.

Instead of addressing structural problems such as rural poverty, the land reform promised in the peace agreement and security deficits, and working for peace, the Duque government often relied on violence and military action. Especially in the upper class of the country, from which Duque comes, there continue to be many opponents of peace, although after many decades of armed violence it is obvious that neither the war against the guerrillas nor the war against drugs in Colombia can be won militarily.

Peace with a new president?

Many Colombians, especially young people, long for peace and hope for the presidential election in May 2022 and a new president. In the polls, Gustavo Petro of the centre-left alliance Pacto Historico was ahead, having already narrowly lost to the incumbent Duque in the 2018 run-off. Petro is seen as a proponent of peace and reconciliation in the country – perhaps the time is finally ripe for this in Colombia.

Where did the weapons come from?

„The weapons come from the USA to Venezuela and from there they cross the border into Colombia. They came on boats on the Catatumbo River. And when there were fights with the army and deaths, we took the weapons from the soldiers. Besides, the Colombian state is very corrupt. When I was in the group, some generals from the police came to the camp: here are weapons, here is ammunition. And when we were in cars with the „goods“, many police checkpoints let us pass, without any problems. Most of the weapons come from the USA. There are all kinds: the R15 (USA), the AK 47 (so-called Kalashnikov, Russia), the 9 millimetre Beretta (Italy), the mini-Uzi (Israel), the railgun, sniper rifles, rockets, …“

Juan Andrés (name changed), 18, was with the guerrilla organisation EPL for four years and now lives in the „children’s republic“ Benposta in Bogotá.[xlvi]

Where do the weapons in Colombia come from?

A large part of the weapons come from the USA; Plan Colombia alone brought military equipment worth several billion US dollars into the country from 2000 to 2015[xlvii], including helicopters, armoured vehicles, drones, small arms and ammunition. According to the Peace Research Institute SIPRI, the main suppliers of major military equipment to Colombia from 1970 to 2020 were the USA, ahead of Germany, Israel and France. Looking only at the last ten years from 2011 to 2020, it was the USA, Germany, South Korea and Israel. [xlviii]

USA: hub for small arms

The USA, the largest exporter of small arms in the world, has become the hub for small arms deals with Colombia and many other countries. Most European small arms manufacturers such as SIG Sauer (D), Heckler & Koch (D), Walther (D), Glock (AU), Beretta (IT) or Krauss-Maffei-Wegmann (D) have established large branch offices and production facilities there.

German gun manufacturer SIG Sauer alone officially produced 2.6 million pistols and 240,000 rifles in the US from 2014-2018. Of these, about one in five pistols and one in ten rifles were exported to countries such as Colombia, India, Thailand or Mexico[xlix] – all countries with armed conflicts and severe child rights violations such as the recruitment of child soldiers. In 2018, SIG Sauer was responsible for 40% of all pistol exports from the USA.[l]

German weapons in Colombia

German weapons are numerous in Colombia, especially SIG Sauer pistols and Heckler & Koch assault and machine guns. Since the 1970s, large quantities of G3 assault rifles, MP5 submachine guns, HK21 machine guns and related ammunition have been produced under licence by the Colombian state arms company Indumil in Bogotá, with the help of Heckler & Koch and Fritz Werner machines, then owned by the German state.

Since 2009, large numbers of SIG Sauer pistols have entered the country, some of them illegally, via the USA. Of more than 120,000 SP2022 pistols delivered to Colombia, almost a third were produced at the German SIG Sauer plant in Eckernförde, delivered to the USA and from there illegally forwarded to Colombia without the permission of the German authorities. For this, three top SIG Sauer managers from the USA and Germany were sentenced by a German court in 2019 to heavy fines and suspended prison sentences, and the company had to pay back 11 million euros in profits from the illegal deal. Based on a criminal complaint filed by the campaign „Aktion Aufschrei – Stoppt den Waffenhandel“ (Action Outcry – Stop the Arms Trade), the public prosecutor’s office in Kiel in northern Germany is currently (2021) investigating SIG Sauer again on suspicion of illegal small arms deliveries to Colombia, Mexico and Nicaragua.

Crimes committed with SIG Sauer pistols

In June 2021, the child rights organisation terre des hommes published a dossier according to which SIG Sauer pistols, including the SP2022, are widely used in Colombia, are traded illegally and end up in the hands of illegal armed groups. Paramilitaries, guerrillas, drug cartels, criminals and army personnel have used the weapons for crimes that have included the use of child soldiers.[li]

Since the end of the 1990s, state-approved arms deliveries from Germany to Colombia have concentrated mainly on the lucrative market for submarines and warships. Small arms according to the German government’s definition have not been exported from Germany to Colombia since then, according to government arms export reports. However, this definition omits numerous types of small arms such as pistols, various types of rifles, hand grenades and others, which can thus undermine export controls.

Germany violates Arms Trade Treaty

The German government’s definition of small arms does not correspond to the much more comprehensive definition of the United Nations, which Germany committed to using when it ratified the Arms Trade Treaty in 2014. [lii] Germany is thus in violation of the treaty.

Arms expert Christopher Steinmetz was able to prove in two studies in 2017[liii] and 2020[liv], using data from the German Federal Statistical Office, that German small arms and ammunition were supplied to Colombia in large quantities from 2002 onwards, which are not listed in the German government’s arms export reports – for example, 16 tons of rifle ammunition and parts for pistols and rifles in the 5 years from 2014 to 2019 alone, and almost 1500 pistols & revolvers and over 600 rifles between 2002 and 2015.

„I learned how to use a compass, attack police stations, set an ambush and handle weapons. I used AK47 rifles (Russia), Galil rifles (Russia), AR-15 rifles (USA), mortars, pineapple grenades, M26 grenades, and „tatucos“ (grenade launchers).“

Ramiro, recruited by the FARC guerrillas at age 15[lv]

War over drugs and land – the armed conflict in Colombia

There have been armed conflicts in Colombia for more than 70 years, since 1948: After the assassination of the liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, who had announced an agrarian reform, a bloody civil war followed, first between the liberal and conservative parties, then it shifted to the rural regions. There, independent peasant republics were founded, which were fought by the state and paramilitary groups of the large landowners. The leftist FARC guerrillas emerged from the army’s crushing of such peasant republics in 1964, and the ELN guerrillas were founded in the same year, both fighting for land reform and equitable land distribution. Other parties to the conflict are the Colombian army and police, right-wing paramilitaries, criminal gangs and drug cartels.

Wealth and poverty are very unequally distributed in Colombia: A small class of large landowners owns most of the land, while the majority of peasants have little or no land. According to the United Nations, 48 percent of the Colombian population was living in „food insecurity“ in January 2021[lvi]. In addition to unequal land distribution, land grabbing, illegal mining, displacement of rural populations – especially Indigenous and Afro-Colombian people – and, above all, the lucrative drug trade are important causes of conflict. All armed groups are involved. Not only paramilitaries, criminal gangs and guerrillas, but also many military officers, politicians and businessmen profit from it. Drug and arms trafficking are closely linked, profits from drug trafficking finance most of the arms purchases of the non-state armed groups. The Colombian army and police have been massively rearmed for decades, mainly by the USA. In addition, military training is provided by US soldiers stationed at several locations in Colombia.

The main victims of the war are the civilian population in the rural regions. Serious human rights violations and killings are commonplace, and all warring parties are involved to varying degrees. Community leaders and human rights defenders, journalists and trade unionists are particularly frequently threatened and murdered in Colombia. At least 220,000 people have already paid for decades of war with their lives, 160,000 have disappeared and more than seven million have been displaced from their homes. Children and young people are particularly affected and are intimidated, threatened and forcibly recruited by guerrilla groups, paramilitaries and drug gangs.

Many girls, but also boys, are victims of sexual violence; perpetrators are not only armed groups, but also soldiers of the Colombian army. According to the public prosecutor’s office, soldiers of the army are also responsible for the murder of 2200 innocent young people, among them many minors, who were falsely presented as killed enemy fighters between 1988 and 2014 in order to feign success against the guerrillas and collect bonuses (so-called „falsos positivos“ scandal). The legal process is ongoing, 24 soldiers have confessed to the murder of 247 people so far.

This is where I learned to dream

„When I was 16, I fled in the middle of the night, I was lucky they didn’t find me. I went to the UNHCR office in Cúcuta. [lvii] I didn’t have any papers and it took a week for them to be ready. During that week I had to hide because they were looking for me. They shelled my mother’s house. Luckily, she was not at home. Then they captured my sister. I had a phone, I had written everything down – how many kilos of what goods were being traded, and so on. They finally said: If you don’t want to come, send us the phone. I sent it. They released my sister and that was it. After a week my papers were ready and UNHCR gave me money for the tickets. Then I came here to Bogotá to Benposta in the Children’s Republic. Everything is very different here. Here I learned to dream. I learned to be free. I learned to say what I like and don’t like. I’ve learned that it’s difficult when you haven’t learned anything. That money is not everything. Money can make you happy, but the people we love the most make us much happier. I am very grateful to Benposta.“

Juan Andrés (name changed), 18, was with the guerrilla organisation EPL for four years and now lives in the „Children’s Republic“ Benposta in Bogotá, an aid project for children and young people affected by war in Bogotá, supported by the child rights organisation terre des hommes Germany. [lviii]

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Interview: „There are many German weapons in Afghanistan“

Jamal had to fight against the Taliban as a child soldier between the ages of 10 and 13. He later fled to Germany via Iran, Turkey and France.

„I grew up in a religious family. My father was a professor, he was an opponent of the Taliban and at some point decided to fight against them, he was a freedom fighter. When I was 7 I had to do field work and when I was 9 my father said to me, „You are a man now, fight with us!“ I didn’t want to and managed to convince him to work as a shepherd for now. But when I was 10 years old, he insisted that I help his armed group, I became a doctor’s assistant. And when I was 13, he said, „Now you have no excuses, now you have to join the fight.“

I learned how to fight and spy. You couldn’t tell who was a civilian, who was Taliban. There are also many German weapons in Afghanistan, the G3 is a good rifle. I was a soldier now. I didn’t know what for. I was with my father in the mountains so the Taliban couldn’t find us. About once a month we went home to visit. The Taliban found out and killed my father, my mother and my older brother.

I was now the eldest at 13 and had to flee with my younger siblings and fend for ourselves. Fortunately, a carpenter hired me as a helper, he was a good man, he saved our lives. Later I heard that he paid me ten times the wages of the other workers. When I was 15, soldiers arrested me, I had no papers and they claimed I was a spy. I was in prison for three months, got almost no food and was beaten every day to make me admit it, that was very bad. My siblings and the carpenter didn’t know where I was at all. My siblings felt abandoned, they say I am a failure and don’t like to talk to me.

At some point, a new prison commander released me and I quickly fled to Iran, where I worked for two years and was able to save a little money. I dreamt of my parents‘ death every night there. At some point I was so desperate and gave up. I took 27 sleeping pills and was in a coma for three days, but I survived. Some time later I walked 160 hours to the Turkish border. There I bribed the Turkish border guards. In Greece, a smuggler then hid me in a lorry container with watermelons, there was hardly any room and I almost suffocated. In France, workers discovered me, they were nice. I then spent some time in Paris and then took the train to Germany, then the police picked me up.“

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━▼━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Ralf Willinger has been working for more than fifteen years as a consultant for children’s rights with a focus on children in armed conflicts and peace work at the international children’s relief organisation terre des hommes Germany (tdh). He has written and coordinated various publications on the subject, is spokesperson for the campaign „Never under 18! No Minors in the German Armed Forces“ campaign, tdh representative at the „Action Outcry – Stop the Arms Trade“ and the „Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict“ and was spokesperson of the „German Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers“ for twelve years. Willinger regularly travels to conflict -affected countries, for example to Colombia, Brazil, Myanmar, the Philippines, India, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, and campaigns for children’s rights and peace together with young people and tdh partner organisations.

Dr. Helmut Lohrer

(born 1963) is a general practitioner from Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany. After working as a teacher in Cameroon for two years, he studied medicine in Heidelberg and completed his specialist training in Manchester/England and in Villingen-Schwenningen. Since his university days, he has been involved with the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) and he is the International Councilor of its German affiliate. In 2013, he organized Human Target, a congress on small arms in Villingen, in which 300 physicians, scientists, and activists from all over the world took part. Contact: lohrer@ippnw.de , +49-172-777 3934

Jürgen Grässlin

is the initiator of GLOBAL NET – STOP THE ARMS TRADE (GN-STAT), spokesperson of the campaign „Aktion Aufschrei – Stoppt den Waffenhandel!“, national spokesperson of the German Peace Society – United Opponents of War (DFG-VK), co-founder of the Critical Shareholders Heckler & Koch (KA H&K) and chairman of the Arms Information Centre (RIB e.V.).

He is the author of numerous critical non-fiction books on arms exports and military and economic policy, including international bestsellers. Grässlin has so far been awarded ten prizes for peace, civil courage, media work and human rights.

Contact: Tel.: 0049-761-7678208, Mob.: 0049-170-6113759

E-mail: jg@rib-ev.de, graesslin@dfg-vk.de

Endnotes

[i] UN Secretary General: Annual Report Children and Armed Conflict (May 2021). The so-called list of shame can be found in the annex of the report.

[ii] These are: Afghanistan, Colombia, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Myanmar, Philippines, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria, Yemen

[iii] These are: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, India, Israel & Palestine, Lebanon, Libya, Niger, Pakistan. The fact that the countries in the list of shame in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report „Children in Armed Conflict“ are divided into different categories, that some conflict actors are not listed despite serious violations of children’s rights documented in the report and that, in addition, many conflict countries are completely missing, has political or procedural reasons, not factually justified ones. See also endnote 20

[iv] According to SIPRI (März 2021). https://de.statista.com/infografik/24412/das-sind-die-groessten-waffenhaendler-weltweit/

[v] Deckert, Roman: „…morden mit in aller Welt – Deutsche Kleinwaffen ohne Grenzen (2008). https://www.iz3w.org/zeitschrift/ausgaben/305_klimapolitik/faa

[vi] Statement during the press conference of the German Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers conference on the occasion of Red Hand Day 2017

[vii] SIPRI Arms-Transfer database as of March 2021 https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers

[viii] Former UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon called them „the weapons of mass destruction of the 21st century“.

[ix] Steinmetz, Christopher: Small Arms in Small Hands: German Arms Exports Violating Children’s Rights (2020). terre des hommes, Brot für die Welt, BITS. www.tdh.de/kleinwaffen

[x] The international Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) entered into force in 2014 and has since been ratified by 110 countries, including China, Canada, Brazil, South Africa, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy. https://thearmstradetreaty.org/treaty-status.html?templateId=209883 . It regulates the trade in conventional arms and, under Article 6, prohibits arms exports that contribute to genocide, war crimes or serious human rights violations.

[xi] E.g. the Political Guidelines for Arms Exports of the Federal Government in Germany

[xiii] European Parliament resolution of 11 February 2021 on the humanitarian and political situation in Yemen (2021/2539(RSP)): https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0053_DE.html , Full Quote: „…Underlines that EU-based arms exporters that fuel the conflict in Yemen are non-compliant with several criteria of the legally binding Council Common Position 2008/944/CFSP on arms exports; reiterates its call, in this respect, for an EU-wide ban on the export, sale, update and maintenance of any form of security equipment to members of the coalition, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE, given the serious breaches of international humanitarian and human rights law committed in Yemen;“

[xiv] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session48/Documents/A_HRC_48_20_AdvanceEditedVersion.docx

[xv] Discussion with representatives of the German Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers, June 2012

[xvi] The first UN document to identify the link between the availability of small arms and the recruitment of child soldiers was the landmark report by Graça Machel, „Impact of armed conflict on children“ (1996), commissioned by the UN Secretary-General.

[xvii] ECCHR (European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights) (Germany), Mwatana for Human Rights (Yemen), Amnesty International (France), Campaign Against Arms Trade (UK), Centre Delàs (Spain) and Rete Disarmo (Italy). https://www.ecchr.eu/fall/bombenangriffe-made-in-europe/

[xviii] The criminal complaint is directed against Airbus Defence and Space GmbH, Leonardo S.p.A., Rheinmetall AG and BAE Systems, among others.

[xix] https://www.ecchr.eu/fall/bombenangriffe-made-in-europe/

[xx] A critical analysis of the list of shame can be found in: “Keeping the Promise: An Independent Review of the UN’s Annual List of Perpetrators of Grave Violations Against Children 2010-2020”. https://watchlist.org/wp-content/uploads/eminent-persons-group-report-final.pdf

[xxi] Langeani, Bruno and Pollachi, Natália: „ Less Guns, More Youth: Armed Violence, Police Violence and the Arms Trade in Brazil “ (2021) Ed. terre des hommes Germany and Switzerland, Instituto Sou da Paz, Brazil. www.tdh.de/polizeigewalt

[xxii] The transitions are fluid, armed conflict actors in countries like Myanmar or Colombia are often involved in the same criminal activities (drug trafficking, arms trafficking, robbery, land theft, often also extortion and human trafficking, etc.) as criminal gangs, and conversely, these are sometimes also involved in political armed conflicts. A prime example are the so-called bacrim (bandas criminales) in Colombia today, which until 2006 operated as paramilitary self-defence groups in the armed conflict („Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia“), were then demobilised by the state in a much-criticised procedure with far-reaching impunity and subsequently partly re-formed and renamed themselves. Since then, they have been called „criminal gangs“ by the Colombian government, although many acted similarly as before. As so-called self-defence groups and also as criminal gangs, they systematically recruited children and young people. Until 2006, these child soldiers were accepted into protection programmes by the Colombian state if they were able to escape, after which they were denied this right by the state because they came from „criminal gangs“. However, after successful protests by children’s rights organisations, it was achieved in court that these children are just as entitled to support and help with reintegration into civilian life as the children who come from guerrilla groups.

[xxiii] The Paris Principles on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups have been signed by at least 105 countries worldwide, including all permanent members of the UN Security Council, except for the USA (China, Russia, France, Great Britain), Germany, Italy, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and Indonesia. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/de/aussenpolitik-frankreichs/menschenrechte-und-humanitare-hilfe/menschenrechte/das-unternimmt-frankreich-zur-forderung-der-kinderrechte/die-pariser-grundsatze-und-verpflichtungen-worum-geht-es/#sommaire_2

[xxiv] https://ceoworld.biz/2021/06/12/these-are-the-worlds-biggest-importers-of-major-arms/

[xxv] Child Rights Forum of Burma: CRC Shadow Report Burma, The plight of children under military rule in Burma. 2011. https://www.burmapartnership.org/2011/04/crc-shadow-report-burma-the-plight-of-children-under-military-rule-in-burma/ (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[xxvi] In the 1950s and 60s Rheinmetall was the main exporter of the G3 apart from Heckler & Koch. Otfried Nassauer: Rheinmetall statt Heckler & Koch. BITS, 2015. https://www.bits.de/public/unv_a/orginal-030915.htm (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxvii] Christopher Steinmetz: Small Arms in the Hands of Children. German Arms Exports and Child Soldiers. . Ed. terre des hommes, BITS et al, 2017. https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/04_Was_wir_tun/Themen/Krieg_und_Flucht/Small_Arms_in_the_hands_of_children_-_terre_des_hommes_Kindernothilfe_Brot_EN_Final.pdf (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxviii] Roman Deckert: …morden mit in aller Welt – Deutsche Kleinwaffen ohne Grenzen, IZ3W, 2008. https://www.iz3w.org/zeitschrift/ausgaben/305_klimapolitik/faa (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxix] V. Kenneth: Burmese Small Arms Development. http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=1154 (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxx] V. Kenneth: Burmese Small Arms Development. http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=1154 (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxxi] Franka Lu: Partner, Alliierter, Investor, Ausbeuter. 2021. https://www.zeit.de/kultur/2021-03/myanmar-china-militaerputsch-einfluss-burma-geschichte-demokratie/komplettansicht (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxxii] https://www.sonnenseite.com/de/politik/militaer-in-myanmar-setzt-deutsche-ruestungsgueter-ein/ (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxxiii] https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/05/global-civil-society-statement-myanmar (Accessed 24.01.2022)

[xxxiv] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/indian-arms-exporter-ships-air-defense-weapons-to-myanmars-junta.html

[xxxv] Source: UN Secretary General’s annual reports on children and armed conflict. Numbers from June 2012 to September 2018 summarized in: UN Human Rights Council, Report of the detailed findings of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, S. 69. Download of the full report: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/FFM-Myanmar/A_HRC_39_CRP.2.docx (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[xxxvi] Innocent: A Spirit of Resilience. (Accessed 24.01.2022). book trailer (German) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDuVYz4tedE, Accessed 24.01.2022

[xxxvii] Iris Stolz / terre des hommes (2020) : Dollars, Drogen und bewaffneter Kampf. Ein Ex-Kindersoldat aus Kolumbien erzählt seine Geschichte. terre des hommes-Magazin 2-2020. https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/10_Material/Magazin/tdh_Magazin_2020-2.pdf

[xxxviii] Ehringfeld, Klaus (2020): Wie Gangs in der Pandemie Kinder zwangsrekrutieren. https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/kolumbien-wie-gangs-waehrend-der-corona-pandemie-kinder-zwangsrekrutieren-a-4fec5337-e329-4497-9054-3df2001cfd8e

[xxxix] The number of undocumented cases of serious violations of children’s rights in armed conflicts, especially recruitment and sexual violence, is estimated to be many times higher than the number of documented cases. Local organisations also often document significantly more cases than listed in the United Nations reports. For example, the „Observatory for Childhood and Armed Conflict“ (ONCA) in Bogotá documented 128 cases of recruitment in the first third of 2020 alone – but the United Nations only reports 116 cases of recruitment in Colombia in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on children and armed conflict for the whole of 2020.

[xl] Ehringfeld, Klaus (2020): Wie Gangs in der Pandemie Kinder zwangsrekrutieren. https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/kolumbien-wie-gangs-waehrend-der-corona-pandemie-kinder-zwangsrekrutieren-a-4fec5337-e329-4497-9054-3df2001cfd8e

[xli] The number of undocumented cases of serious violations of children’s rights in armed conflicts, especially recruitment and sexual violence, is estimated to be many times higher than the number of documented cases. Local organisations also often document significantly more cases than listed in the United Nations reports. For example, the „Observatory for Childhood and Armed Conflict“ (ONCA) in Bogotá documented 128 cases of recruitment in the first third of 2020 alone – but the United Nations only reports 116 cases of recruitment in Colombia in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on children and armed conflict for the whole of 2020.

[xlii] Büro des Hochkommissars der Vereinten Nationen für Menschenrechte (OHCHR)

[xliii] https://amerika21.de/2021/12/256048/uno-bestaetigt-52-tote-kolumbien-proteste

[xliv] Ehringfeld, Klaus (2020): Wie Gangs in der Pandemie Kinder zwangsrekrutieren. https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/kolumbien-wie-gangs-waehrend-der-corona-pandemie-kinder-zwangsrekrutieren-a-4fec5337-e329-4497-9054-3df2001cfd8e

[xlv] Büro des Hochkommissars der Vereinten Nationen für Menschenrechte (OHCHR) (2021): El paro nacional 2021: lecciones aprendidas para el ejercicio del derecho de reunión pacífica en Colombia. https://www.hchr.org.co/documentoseinformes/documentos/Colombia_Documento-lecciones-aprendidas-y-observaciones-Paro-Nacional-2021.pdf

[xlvi] Iris Stolz / terre des hommes (2020) : Dollars, Drogen und bewaffneter Kampf. Ein Ex-Kindersoldat aus Kolumbien erzählt seine Geschichte. terre des hommes-Magazin 2-2020. https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/10_Material/Magazin/tdh_Magazin_2020-2.pdf

[xlvii] The USA’s Plan Colombia totalled around 10 billion US dollars from 2000-2015, the largest share of which was spent on armaments and military aid. Otis, John (2014). The FARC and Colombia’s Illegal Drug Trade. Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/Otis_FARCDrugTrade2014.pdf

[xlviii]The Swedish Peace Research Institute SIPRI analyses all available data on transfers of major weapons worldwide in its database. https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers

[xlix] Steinmetz, Christopher (2017): Small Arms in the Hands of Children. Ed. terre des hommes, KNH, BITS et al, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/RuleOfLaw/ArmsTransfers/TerreHommesKindernothilfe.pdf, German: https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/04_Was_wir_tun/Themen/Krieg_und_Flucht/Studie_Kleinwaffen_in_Kinderhaende.pdf

[l] Annual Report 2014-2018 of the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco Firearms and Explosives

[li] terre des hommes (2021) : Dossier SIG Sauer-Pistolen in Kolumbien. https://www.tdh.de/was-wir-tun/arbeitsfelder/kinder-im-krieg/materialien-links-adressen/

[lii] Arms Trade Treaty), Paragraph 5.3. “Each State Party is encouraged to apply the provisions of this Treaty to the broadest range of conventional arms. National definitions of any of the categories covered under Article 2 (1) (a)-(g) shall not cover less than the descriptions used in the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms at the time of entry into force of this Treaty. For the category covered under Article 2 (1) (h), national definitions shall not cover less than the descriptions used in relevant United Nations instruments at the time of entry into force of this Treaty.

[liii] Steinmetz, Christopher (2017): Small Arms in the Hands of Children. Ed. terre des hommes, KNH, BITS et al, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/RuleOfLaw/ArmsTransfers/TerreHommesKindernothilfe.pdf, German: https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/04_Was_wir_tun/Themen/Krieg_und_Flucht/Studie_Kleinwaffen_in_Kinderhaende.pdf

[liv] Steinmetz, Christopher (2017): Small Arms in the Hands of Children. Ed. terre des hommes, KNH, BITS et al, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/RuleOfLaw/ArmsTransfers/TerreHommesKindernothilfe.pdf, German: https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/04_Was_wir_tun/Themen/Krieg_und_Flucht/Studie_Kleinwaffen_in_Kinderhaende.pdf

[lv] Human Rights Watch (2003): You’ll Learn Not To Cry – Child Combattants in Colombia., p.. 62

[lvi] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (2021): El paro nacional 2021: lecciones aprendidas para el ejercicio del derecho de reunión pacífica en Colombia. https://www.hchr.org.co/documentoseinformes/documentos/Colombia_Documento-lecciones-aprendidas-y-observaciones-Paro-Nacional-2021.pdf

[lvii] UNHCR: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

[lviii] Iris Stolz / terre des hommes (2020) : Dollars, Drogen und bewaffneter Kampf. Ein Ex-Kindersoldat aus Kolumbien erzählt seine Geschichte. terre des hommes-Magazin 2-2020. https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/10_Material/Magazin/tdh_Magazin_2020-2.pdf

https://www.tdh.de/fileadmin/user_upload/inhalte/10_Material/Magazin/tdh_Magazin_2020-2.pdf